Where exploring country takes you back 90 million years

Located on the banks of the Bulloo River, 980 kms west of Brisbane, Quilpie is a quaint country town, servicing 600-700 Queenslanders.

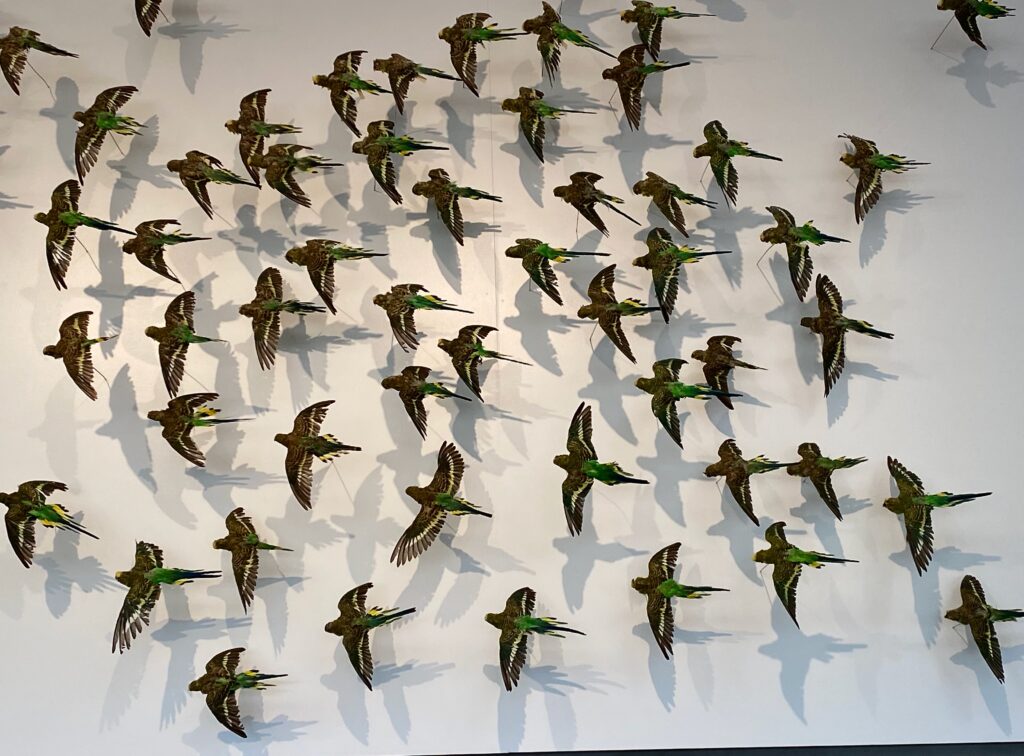

The name Quilpie is derived from the Aboriginal word “Quilpeta”, the secretive bush Stone Curlew or “Thick Knee”. A native bird species, not often seen given its camouflage capacities but identified by its eerie screeching, wailing calls at night.

Aboriginal cultures suggest the call is associated with death, or a sign of imminent change in the weather. In other desert regions an indication of Dingo visitations.

Quilpie, the town of 1917, is nature oriented with all but four of its streets named after native birds. On our 14 day Corner Country Outback Tour, we overnight in the town while exploring the broader Quilpie Shire. Here are some memorable discoveries.

The Bulloo River

This slow flowing river, 600kms long, is an isolated drainage system originating north of Quilpie and following occasional flood events, terminating in a swampy flood plain across the border in New South Wales. We visit the Bulloo River early in the tour, at the town of Thargomindah.

Unlike all other rivers in the area it does not flow into either the Murray-Darling or Lake Eyre Basins. Usually, it is completely dry with occasional ponds and small temporary lakes left to support the wildlife.

However, when it floods the Bulloo River turns on a show, filling the terminal swamps, supporting several hundred thousand waterbirds enjoying a timely migration.

It was on the Bulloo, in 1860-61, four members of the Burke and Wills Expedition died of scurvy and privations of isolation.

Quilpie is one of only two outback service centres in the Bulloo Basin and can suffer from extreme drought periods, dependent on an average 300mm annual rainfall and mean maximum temperatures of 38C. Dry years with only 100mm of rain or zero runoff are experienced.

World of Diprotodons

West and south of Quilpie in the flood plains, forests and grasslands, between the villages of Eromanga and Eulo (Pop 30) the great vegetarian megafauna and Australia’s largest marsupial, once roamed.

The Diprotodon was like a huge wombat over 2 metres tall and weighing 2 tonne. It fed on luxurious vegetation as climate was slowly changing the landscape to less nutritious hardy shrubs.

Diprotodons ranged across inland Australia for tens of thousands of years, co-existing with the Australian Aborigines following their arrival. These Eulo megafauna lived approx 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, becoming extinct about 25,000 years ago.

Fossilised skeletons of 40 to 50 giant Diprotodons have been discovered by university and museum scientists between Eulo, Eromanga and Quilpie, the largest concentration of the creatures anywhere in Australia.

They had a rear facing pouch able to carry the equivalent of a small child, an over-sized head and walked pigeon toed.

Roaming semi-arid open woodlands free of hilly country, they ate 100 to 150 kilograms of vegetation a day, using chisel-like incisors to uproot the vegetation.

As Aborigines did not hunt with big game weapons, the argument prevails that climate change may have caused the Diprotodon’s extinction.

World of Dinosaurs

Eromanga (Pop 40) is a small town west of Quilpie, once called “Opal Opolis” given its history of opal fossicking. It looks a little tired but is celebrating a new phase through the discovery of Australia’s largest dinosaur, a Titanosaur.

Officially named “Australotitan Cooperensis” or affectionately “Cooper” after the Cooper Creek and Basin

It is apparent these creatures lived on the edge of the vast Eromanga Inland Sea which existed 65 to 145 million years ago.

Remains of “Cooper”, thought to be 95-98 million years old were stumbled upon by a 14 yr old son mustering cattle on his father’s property. “Cooper” also has mates called “Zac” & “George”.

The find, along with 70 or so other dinosaur and megafauna sites in the region (most left in location for security), has prompted the impressive development of the Eromanga Natural History Museum, an educational and tourism facility showcasing a diverse range of fossils from tiny micro-fauna to the enormous “Cooper” in scale.

Here is an arid Australia “centre of excellence” working hub for passionate palaeontologists and public alike. Including active field and technical programs focused on prehistoric natural history before dinosaur extinction 64 million years ago.

“Cooper” is estimated to have been 25 – 30 metres long, 5-7 metres high and weighing between 22 and 50 tonnes, with largest bones 1.5 metres and weighing 100kg

Our tour of the museum takes in the discovery story, an understanding of times and species, hands on demonstrations of technical recovery and restoration of the bones, plus racks of bones in large casts awaiting years of painstaking technical unveiling.

Duracks of “Thylungra”

Our tour passes through the historic “Thylungra” sheep station located 100 kms north-west of Quilpie, open downs “flood-out” country, originally established by pioneering cattle grazier and Irish immigrant, Patrick Durack.

The best selling book “Kings in Grass Castles” by his grand-daughter Dame Mary Durack has been acclaimed as “classic Australian literature”. It tells of Patrick and the Durack family hoofing their cattle into the tropical north and contact with the Aboriginal peoples.

In 1882 Patrick left Thylungra on an epic two and a half year cattle drive to establish Argyle Downs Station in the Western Australia, Kimberley region. ”Overlanding” with 7250 head of cattle and 200 horses, his 4,828 kms journey saw the loss of half the stock and Durack pursued with legal action for commission not paid on the sale of Thylungra.

There was a major shearers strike on Thylungra in 1910 and following improved equipment and conditions 100,000 head of sheep were shorn in a year. In 2008 the station sold for $10.5 million.

Boulder Opals and pub with no town

The Opal has been hailed as Australia’s official gemstone, filling 96% of the world’s demand for commercial grade stones. The Boulder Opal beauty and durability is attributed to its ironstone backing or “host”.

Father of the boulder opal industry, the late Des Brown was a miner and retailer who took Australian opals to the world stage. He donated opals for an iconic display at Quilpie’s St Finbarr’s Church, adorning the altar, lectern and baptismal font.

The glass windows of the Church were donated by Dame Mary Durack in memory of her famous ancestors.

Boulder opal fields are located in an extensive vein 1000kms long and 300 kms wide extending from Hungerford on the New South Wales border through to the NW Queensland town of Kynuna.

Boulder Opal mining began in 1890 with open cut and underground mining. While Quilpie is regarded as the opal town there exists many dormant and active fields including hand mining near the town of Toompine (Pop2), once a bustling mining centre and Cobb & Co Coach changing station.

Today Toompine is reduced to an old pub with no town.

Boulder Opals can range in size from a few to 20 centimetres.

Mulga Lands

There are 800 or so Acacia (Wattle) species in Australia, Mulga being one of these and named after a small flat shield used by our First Nations People.

The species grow in an extensive landscape of dry sandy, largely infertile plains. It is a very hardy bush/tree able to survive Australia’s dry climate, low rainfall and heavy drought periods.

The Great Artesian Basin sits under the Mulga Lands and occasional mounded springs provide water for unique wildlife.

Most of the lands are used by farmers for sheep and cattle grazing of accompanying grasslands and in drought periods Mulga leaves and bushes are stripped and used for high protein livestock fodder.

In fact some farmers will claim, given long term drought events, their livestock have never known a blade of grass, eating only Mulga.

The plants grow at a slow rate of approximately one metre every ten years.

While the casual visitor rushing through Mulga country may not be so excited by the “perceived monotony” of the vegetation, the immersive story is an extraordinary one, considering the demands of survival for the species.

Indeed we take time on our Corner Country Outback Tour to highlight the resourcefulness of the plant and its historic importance to First Nations People.

The Mulga utilises every drop of moisture it can capture with its foliage designed to channel all water down toward its deep tap roots. Thin silvery grey foliage is designed to minimise moisture loss in heat and sun.

A plant with just 10 cms growth will have a moisture searching tap root 3 metres deep.

Aborigines would separate the seed from its pods and process these into an eatable paste.

Sweet secretions collected and dissolved in water created a sweet drink.

A white powdery substance on the leaves was collected to create resin for tool parts and repairs.

The Mulga wood was used to make spear throwers, boomerangs and tough digging sticks.

There were applied healing qualities for colds, flu and a cleansing wash.

Post natal therapy involved mulga branches being placed over hot coals on which mother and child would lay asleep with smoke and vapour enveloping their bodies.

The Mulga carbon farming dilemma

Above ground carbon in mulga vegetation is stored in living trees and shrubs, retaining 30 to 150 tonnes of carbon dioxide per hectare.

Large trees hold far more carbon. Retaining strips or blocks of Mulga on properties lead to an increase in carbon storage.

While promoted as a means to combating climate change , reports from the Quilpie Shire suggest carbon farming in Mulga Lands is changing community foundations.

Corporations are buying up large tracks of Mulga land for revenue earning carbon storage and “off-set schemes”, in doing so locking the land up.

Owners and workers on farms are removed under lock up and no one lives on the farms.

Corporations don’t work the holdings, fuel and farming supplies are no longer purchased, families leave the farm and region, mail runs close, schools down size or close, police leave and town centre shops and businesses close down. Wild dog and feral pigs roam the country freely adding to shire damage and costs.

Any income earned in carbon capture schemes is not passed through to suffering Shires.

A neighbouring Shire to Quilpie has lost 400 people in eight years, a telling impact given the Shire’s population in 2018 was only 1586 people.

The concern remains, does carbon farming have a future in a Shire like Quilpie with only 600 to 700 people?

Discover the spirit of outback Australia, across the legendary Corner Country

Nature Bound Australia has conducted regular visits to outback Shires and towns across the Corner Country since 2008, featured in our 14 day Corner Country Outback Tour.

Tour highlights include the authentic western towns of Quilpie, Thargomindah, Tibooburra, Innamincka, Birdsville and Windorah. Also the Sturt and Malkumba-Coongie Lakes National Parks; Strzelecki, Sturt Stony and Simpson Deserts; Charles Sturt and Burke and Wills Expedition sites; legendary rivers and wildlife corridors like the Bulloo, Paroo and Diamantina plus Cooper Creek.